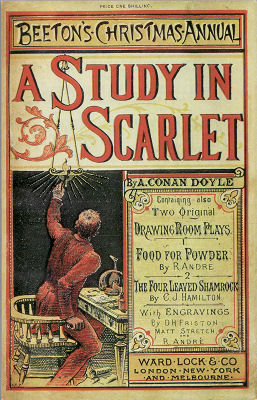

Arthur Conan Doyle -- A Study In Scarlet

What makes a work of fiction echo down the ages, relevant to all who read it?

How can you craft a story, or a book, or a script that will resonate cleanly to readers who come to your work after you have left the stage?

A few thoughts…

Consider the works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

What is the difference between the first Sherlock Holmes novel—A Study in Scarlet and Doyle’s 1891 novel, The Doings Of Raffles Haw?

One sits in the golden path of the world’s great mystery novels, and the other… well, I’m reasonably certain you’ve never heard of it.

In Scarlet, Sir Arthur begins by detailing the life of John H. Watson, M.D., veteran of the second Afghan War, recuperating in London. An interesting character, sympathetically described, who meets his roommate-to-be, a man who greets him and immediately says, “You have been in Afghanistan, I perceive.”

What has begun as the reminiscences of an Army surgeon twists into a mystery… Holmes meets Watson and the game, as they say, is afoot.

The Doings Of Raffles Haw begins as a mundane tale of fiscal and family woe, and in a chapter or two slowly changes to a fantasy about unlimited wealth and its uses. The characters are utterly forgettable.

Points: Sharp, interesting characters, doing interesting things. Amaze your reader.

Both are set in approximately the same period. Both have plots with secrets revealed, and human failings set in a Victorian prism.

Both in their own way are fantasies.

One tale illuminates its period, and the other is just a shadow of its time.

–William V. Burns

Project Gutenberg links to both novels: