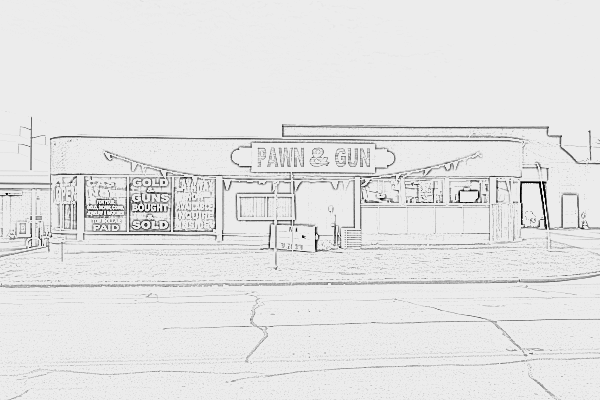

It was my summer job, working with old man Jenkins at the Pawn & Gun. I just swept up, polished the sweaty fingerprints off the glass in the cases, opened boxes and stomped them flat to fit in the dumpster behind, and many other such chores. I didn’t get to sit behind the counter with the guns and watches and jewelry and all the glittering things. That was Mr. Jenkins’ privilege as owner. At the time I envied him his throne.

The shop was huge to me, and like a treasure trove, with the jewelry and gold and silver sparkling from end to end of the glass cases that formed the counter, with old man Jenkins sitting behind it all on his swivel stool, register right behind him in the center. He had a big pale green paper blotter on the counter in front, where he’d put the object, whether a watch or ring or coin, while he discussed a deal with its owner.

I would stop sweeping at first, and watch and listen to Mr. Jenkins smile and speak softly and amiably to a customer, whether buying or selling, genuine friendliness in his voice, but with an unstated savvy behind his figuring and offers. By the second or third week, though, I’d quickly resume when Jenkins would cock his head at me while he was negotiating, showing me he’d noticed. He was kind but firm with me about getting his two dollar’s worth out of each hour I worked. “It takes a certain amount of money to keep the shop profitable, Sam, and I can only make so much from a small town like ours.” He was always going over the store’s books when business slowed, and then slide them away under the register when the bell on the door went ding.

In high school, we’d studied Greek Mythology, and I’d listened because the stories were so fantastic. My favorite was about the Fates, three sisters who spun the threads of each person’s fate into our common destiny. In their hands, as they sang and wove were a man’s, or a woman’s, or a child’s fate, and they determined what happened to each.

Soon I realized that old man Jenkins also held the threads of people’s lives in his wrinkly hands, even with his ever-present smile, because I would see how people used the store to see them through life’s high and low points. A couple in love would come in and shop for a set of wedding bands, alcoholics would pawn something every day to feed their habits, a man whose paycheck didn’t stretch far enough would bring in something, maybe a clock, or his father’s watch, and put their immediate future in old man Jenkin’s hands as he put his jeweler’s loupe to his eye, a bright light on the item of value, and hum lightly as he evaluated it. Then he’d lay it down on the blotter and softly announce what he’d give for it, either in pawn or sale.

I saw people pawn the prized jewelry of their dead mother to help bury her, and another pawn his gun to buy a bassinet. And… once a nervous, jittery man with thick curly hair and a thick jacket not well-suited for a hot summer day came in and asked to see a rack of gold bracelets and reached under that bulky jacket, only to see genial Mr. Jenkins unsnap his holster, the holster that held his Colt .45 ACP pistol — he’d bought it after his service in Korea as a Marine. The nervous man turned around and left the store without a word. Mr. Jenkins thought for a moment, and then turned and picked up the phone and called the police. Only then did his smile return.

Threads were paid out like lifelines but sometimes snipped off short too. A man who had pawned his wife’s jewelry, being told the goods were sold, long after his loan was due, long after many letters were sent, asking in a low moan, “How am I going to tell my wife? She trusted me.” A man just short of his rent bringing in a phonograph to sell, and Jenkins sadly shaking his head no. So many sad times in a pawn shop.

One unseasonably cool June evening I heard Mr. Jenkins get philosophical about the effect his business had on his customers. He’d just bought a fancy guitar from a college coed home for the summer. Her ex-boyfriend had bought it for her and she couldn’t stand seeing it around. “I love playing, and I want to get better, but having the guitar… it hurts every time I see it,” she said. Mr. Jenkins bought the guitar, hung it up, and persuaded the girl to keep playing, and offered her another less fancy guitar at a good price. When she left the store, a bit happier, he said, “People bring me their problems and I give them what I can. Sometimes advice, sometimes cash, and rarely, redemption.”

Pawn & Gun was seasonal, I found out during my three months there, as a burly gentleman in jeans and a flannel shirt came into the shop my first week and paid off his loan, interest and fees and all, and reclaimed his carpenters’ tools, a yearly ritual for him. Hunters came in just before fall to look at shotguns and jackets, and in the back lot, there were a couple of boats that made their way back to the water of our nearby lake that summer.

But there were circles of thread that trailed only down, down, down, as I soon found out. In my first week, there was a Mr. Palmer in to sell some antiques that belonged to his parents, and he muttered low to old man Jenkins, who wrote up his ticket for sale. He started coming in every month, sometimes more often, and he sold jewelry, a coin collection, and so much more valuables over the weeks that I thought for sure he had a bad habit, like cocaine, as he became visibly thinner in the summer I worked at the Pawn & Gun.

It was Labor Day, and Mr. Jenkins was paying me my last wages before I went back to school, shaking my hand and telling me he hoped to have my help again in the holidays, when Mr. Palmer shambled unsteadily into the Pawn & Gun, his face yellow and drawn. He smiled at me, but it was a smile of lips and teeth only, nothing in the eyes. I looked at something else, I had to, his eyes were empty, like none I’d seen before.

“Hey Sarge, I’m looking for something in the way of protection. Had a break-in last night.” Jenkins looked closely into Mr. Palmer’s eyes, and spoke slowly, low but clear. “Now, you know, Carl, nobody calls me that unless they’re reminding me they served too. You know I won’t give you much advantage as an ex-Marine. Call me Matt, like you did before.”

They discussed guns for a few minutes, about caliber, and type, and grip and finally Mr. Palmer purchased a .32 Browning revolver and a box of ammunition. The purchase was tucked neatly into a brown paper bag and stapled shut like a package. Then old man Jenkins did something very odd to me. He stood up, walked around the counters, and hugged Mr. Palmer. The doorbell dinged as Palmer left.

Mr. Jenkins sat down, looked at his hands, and thoughtfully said to me, “Sam, you know we’re going to get that one back soon.” I asked, “You mean Mr. Palmer?” He blinked once and looked at me with a worn-out expression. “No, son, I mean the gun. Carl Palmer has late-stage liver cancer, and he’s at the end of his rope. I imagine his son will come back to our town to bury him, and of course, he won’t want to have it around… to remind him.”